Barrier Blocks: Lifesteal Season 4, a Study in Conflict

26 April, 2024 / 22,499 words

This is part two of Barrier Blocks, my series on Minecraft roleplay and the fourth wall. It’ll probably make more sense if you read the introduction first.

- What's going on here?

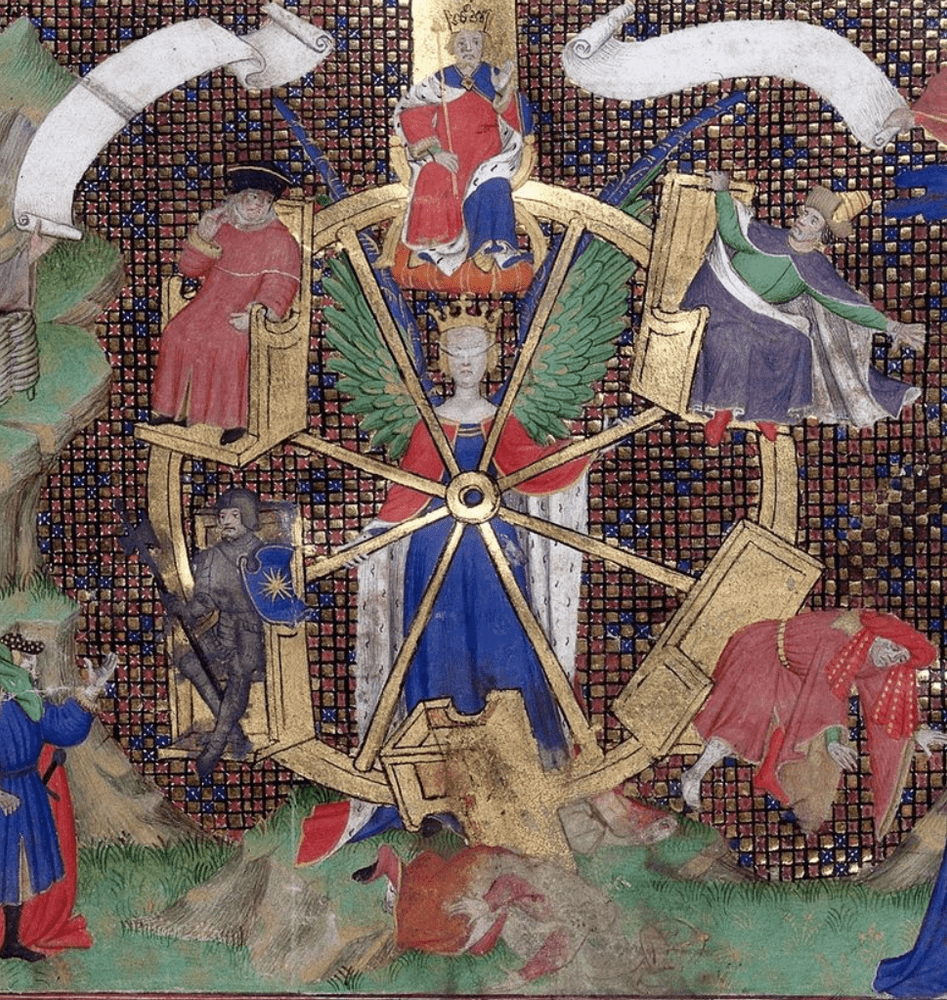

- Rota Fortunae

- In their particularity

- Medium Conflict

- Out of bounds

- The doorway

- Immersion Conflict

- Negation

- Door ajar

- No other but an intrinsic meaning

- In the end

- Postscript

Now, at this point you might have picked up on the fact that I really like Lifesteal. Aside from 3rd Life, it’s probably my favorite Minecraft roleplay I’ve ever seen. For good reason, considering that at the heart of it, Lifesteal Season 4 is a narrative about the very same thing this series is about; the fourth wall. The barrier between game and self, the constructed nature of that barrier, and its inevitable points of failure.

It’s also much more niche. Not that Lifesteal isn’t successful on Youtube; it is, but the version of Lifesteal I'm talking about is the one you get if you sit down and watch through several hundred Twitch vods, some of which are only available on the Internet Archive. Nobody on Lifesteal acts like they ever expect you to want to watch Lifesteal this way, and it’s only possible in the first place because of concentrated archival efforts by a relatively small group of fans.

This is because, for the most part, Lifesteal members are firmly Youtubers before they are streamers. Everything done on Lifesteal is done with a Youtube video in mind as an ideal end-goal. If a Youtube video doesn’t come out of it, or doesn’t come out the way it was meant to, the creators involved in the storyline tend to receive this as a failure.

Part of the preference for videos over streams might also be because the livestream medium is held in constant tension with the way that roleplay on Lifesteal works…

If asked to rank the 5 seasons of Lifesteal, PrinceZam will put Season 4 last, and I don't blame him. He'll also admit that it is, regardless, beloved to many fans. He can guess at why; people are attached to the character dynamics, people who prefer streams over videos enjoyed the density of livestreams. These are not bad reasons, and they are part of why Season 4 has such an enduring place in some people’s hearts, but they also fail to even begin to scratch the surface.

What do we mean by “seasons”?

If you’re unfamiliar with Minecraft Roleplay, this might be confusing. In television terms, you think of a season as a series of episodes broadcast within a certain time period, often with storylines written with these break-off points kept in mind for tying off loose ends or setting up a future plotline. But here, our episodes aren’t written in advance. In Lifesteal’s case, we don’t even necessarily have episodes so much as stand alone videos that can take upwards of a year in production and editing time, depending. For a Minecraft survival multiplayer server (or “SMP” for short), though the specifics can vary from series to series, a new season first and foremost means a new world. At a certain point in the server’s lifespan, builds will have been built, resources will have been extracted, battles will have been fought, things will have been destroyed and repaired and destroyed again. The world will start feeling full, and the players will want the chance to do it over again.

It’s also a natural occasion for old players to leave and new players to join, for rules to change, and on Lifesteal, for the teams to get shuffled around. When a season is complete and you’re looking back on that version of the server, its world, its players, its relationships, and what happened within it, something of a complete story can be seen in retrospect. This isn’t to say that relationships and storylines from seasons past cease to matter as time moves forward—the move from one season to the next isn’t a hard reset, where people act like they’re meeting each other for the first time. It all still matters, it’s just that you might look back on it the way you look back on things that happened to you when you lived in a different place.

I had been passively aware of Lifesteal Season 3, and watched a decent chunk of those videos as they came out, but none of it grabbed me. Season 3 and Season 4 feel very different, in large part because Season 3 is… mostly Lifesteal running smoothly. There are dupe glitches and exploits, brief periods where godhood is achieved, there are anxieties about player activity and the server dying. These are all things that will be amplified in Season 4, but more than any of that, Season 3 is interested in exploring the implications of Lifesteal’s basic game mechanics in and of themselves: What does it mean to have an economy of power? What do you have to do to survive as someone powerless in that economy? Who do you ally yourself with and who do you betray in exchange for that security? Is equality possible through a negation of the heart differentials built into the Lifesteal plugin, a forced return to vanilla Minecraft’s even heart distribution, through redistribution? And so on. They even call their teams The Communists and The Capitalists for a while there.

(A fan video: the events of Lifesteal Season 3 edited together to the song Na Na Na by My Chemical Romance.)

In contrast, Season 4 is Lifesteal getting hijacked in service to a plot to fuck up a Minecraft server visibly enough that Mojang would have to fix a dangerous bug that had been left quietly built into the game for a decade (or at least, this is what Vitalasy will tell you he was trying to do if you ask him, depending on when you ask him). At its heart Lifesteal is a PVP server, but by May of 2023—9 months into Season 4's 10 month lifespan—nobody had fought anyone in two months. Where the fighting used to be, streams were mostly spent standing around arguing with each other about personal morality, the ethics of prisons, and the health of the server at large.

Crucially, everyone still looks back on the final arcs of Season 3 as one of Lifesteal’s highest points, if not the highest. But by the end of it, Lifesteal Season 4 is not well executed, and (almost) no one is happy. Few of the big ideas that go into it come to fruition in the way anyone wanted them to. But, because the characters as they exist on the server are intertwined with the players as storytellers, the tensions between them manifest in a game of tug of war over the course of the story itself. Their anger at each other stems from disappointment over how their big, spectacular plans fail to reach completion. Their misery is created through the grasping at straws trying to transform these failures into entertainment, when the only thing left for your character to do is react to that disappointment. The story doesn't stop in its tracks when it fails, and there's no do-over; you take what you get and you build on it best you can.

As a result, the object becomes not a failed story, or a bad story, but a very good story about failure. And uniquely, one that is not hurt but heightened by the sense that it is in constant conflict with the medium through which it is being presented, without which something like it could not have happened in the first place. In other words, this is something no one would ever make on purpose.

Rota Fortunae

Let’s get the basics out of the way: upon killing someone on the Lifesteal server, you steal one of the hearts off of their health bar up to a maximum of 20—that’s double the 10 hearts vanilla Minecraft gives you. On the other side of things, If you lose all of your hearts down to zero, you’re banned from the server. Not permanently banned; expensive custom items can be crafted to ‘revive’ banned players, but you can think of it more or less as a drawn out hardcore gamemode. Given these core mechanics, it’s obvious that Lifesteal is a PVP focused server, and this means that the stories produced by it revolve around conflict. But there has to be a reason to fight, both in service to the quality of the story coming out of it, and the investment driving the players to bother fighting in the first place. This means that no matter how big and how powerful you get it has to be possible to defeat you, so that things can keep moving in the end. Everything is a balancing act. Lifesteal works in cycles…

What happens if you make yourself effectively undefeatable? What if this power is supposed to be slowly built up, incrementally revealed to avoid just that, and then the curtain drops months too early and suddenly, none of that matters anymore?

Bacon: Why do you wanna stop the endless cycle? What does he have against the endless cycle?

Planet: Yeah, the cycle is fun!

Bacon: The cycle is what makes Lifesteal fun and interesting.

Zam: I don’t have a problem with the cycle! He does! And I trust Vitalasy! So—maybe, I don’t know…

Bacon: What do you even agree with him about?

Jaron: What’s—what are we replacing the cycle with?

Zam: I don’t know! I DON’T KNOW!

Bacon: Then why—why are you on his side?

(Bacon vod, 3/26/2023, 1:46:40)

The next thing anyone will tell you about Lifesteal, after that basic concept, is that it isn’t scripted. You can’t base your storytelling from step one on authentic contests of strength and cunning through Minecraft PVP battles, traps, and schemes, if the winners and losers are decided in advance. And that’s what scripting refers to here, outcomes. Everything Lifesteal does, they do in search of authentic reaction; genuine victory, genuine defeat, and genuine surprise.

The secret-keeping and later revealing of information is the bread and butter of storytelling on Lifesteal. The reveal is ideally spectacular and video-worthy, because when you've abandoned the realm of linear, episodic storytelling—the sort you might find in Hermitcraft, or the Life Series, or any oldschool let’s play—a Youtube video has to be built around a hook. Lifesteal videos archetypically condense wide spans of time down into single videos, stringing events together with retrospective voice-over explanation that leaves little room for in-depth character interaction, drawn out conversation, or any of the quiet moments between the drama that really make stories stick. Or, they’re as short as eight minutes long, and paced accordingly. I have a hard time remembering what happens in a Lifesteal video after I’ve seen it, because of how much information is thrown at you at once, and how much of it doesn’t really matter to me when it’s presented this way.

It’s not that they’re bad videos, they’re extremely successful within their niche on Youtube, and very good at being the kind of videos they try to be. As may be obvious judging by the thing you’re reading right now, I have markedly different priorities than most people who might click on one of these. But to me, a Lifesteal video feels incomplete—more like a tool with which to better understand the player who produced it than a stand alone product—and that’s where the livestreams come in.

Incentive Conflict

There are two competing incentives in play when it comes to the style of a Lifesteal Youtube video. On one hand, you have the things that hook people; personality, character interaction, interpersonal drama, interpersonal relationships, and the storylines comprised of these elements. This is the appeal of any classical Minecraft SMP video, any let’s play, and it’s why Lifesteal has the dedicated stream audience that it does have.

Early into Youtube’s history, the only selling point any Youtuber possessed was their personality. But, as Youtube grew to form an industry in its own right, granting anyone at all monetary success if they could just play well enough with the site’s algorithm, Youtube videos as objects began bending themselves to the will of that algorithm over the tastes of any individual, human audience.

Lifesteal is downstream of a generation of Minecraft youtubers who, forgoing the conventions of older episodic let’s play videos, were instead interested in gaming the Youtube algorithm and optimizing their videos for success inside of it. What you get when you take this approach to its furthest extreme is something like Mr Beast’s work, intentionally devoid of personality, because personality can potentially polarize an audience–seeking the widest reach, with the least possible offense to anyone’s sensibilities. The resulting product is nothing whatsoever.

As a Polygon article describes it, concerningly:

[Mr Beast] described spending countless hours obsessing over every detail, down to the optimal brightness of a YouTube thumbnail. He knows the first 10 seconds of a video are the most important for retention, which is why his videos start with a barrage of all the wild things that will unfold in its run time. And that signature MrBeast editing style that’s fast, frantic, and omnipresent on YouTube is a relentless gambit for your attention. “I can get 100 million views on a video for less than 10 grand if I wanted to,” Donaldson boasted (...)

In reviewing dozens of MrBeast videos from over the years, Donaldson has nearly erased himself as a person from his episodic output. If viewers don’t really see him having fun, that’s by design. Donaldson has outright said he sees “personality” as a limitation for growth, once noting in a podcast that hinging your content on who you are as a person means risking not being liked. And if someone doesn’t like a creator as a person, they may not give the videos a chance.

McLoughlin’s comments hit at another bleak possibility: Viewers may hardly see MrBeast having fun in his videos because he’s not actually having a good time. In podcasts, Donaldson tells hosts that he goes so hard, he won’t stop working until he burns out and isn’t able to do anything at all. With a laugh, he admits that he has a mental breakdown “every other week.” If he ever stops for a breather, he says, he gets depressed. MrBeast is so laser-focused on generating content on YouTube that he describes his personality as “YouTube.” He acknowledges that this brutal approach to videos, which has cratered many creators over the years, is not healthy. “People shouldn’t be like me. I don’t have a life, I don’t have a personality,” he said in a podcast recorded in 2023.

Minecraft Youtubers who rose to popularity during the period of COVID isolation, like Dream, treated Youtube as a game to be beat, and were immensely proud of their ability to succeed within that system, seeking this kind of optimization–the same face in every thumbnail, the same title conventions, where the only thing that matters is whether or not someone will click, not the aesthetic value of these elements in relation to the video itself, or the information they give you about it. This is dictated entirely by material incentives: it’s what does well on Youtube, and Youtube is a job–PrinceZam, for example, says that he makes no considerable money streaming, rather he treats it as a hobby. If he needs money, he uploads a video.

Lifesteal videos aren’t Mr Beast, but they aren’t free from that monetary incentive towards certain stylistic choices, either–like I said, nothing is allowed to be episodic. It’s always a video before it's a story.

The most puzzling aspect of the Lifesteal video style, to me, is the reliance on voice lines and replay shots retelling events over the use of stream clips or actual recordings of the game. Neither of these elements are inherently bad and each can have their place, but the energy captured in a good clip, the dynamism, is abandoned in favor of something that is both less compelling and–this is what I can't wrap my head around–more work. When stream clips are more heavily utilized, it’s usually in a video posted to a second channel, kept cordoned off out of fears over main channel videos doing poorly, or simply because they’re devalued in the mind of the creator for requiring less work to produce.

There’s also the matter of pacing. Livestreams work to produce compelling stories because they allow for natural pauses, relative lulls in conversation, the moments between dramas where a character is alone with themselves and allowed to reflect on what’s happening to them. This style of Youtube video is, in comparison, deathly afraid to allow energy to wane for even a moment. They are barrages of information, they start out running and never slow down for even a moment in which to catch your breath. When livestreams have pacing issues, they are issues of the polar opposite kind; too slow, too much repetition.

(A sampling of Lifesteal video titles and thumbnails.)

Where some Minecraft series are easy to interpret as a world in and of themselves, cordoned off from their nature as Minecraft servers—as game-worlds that can be turned off, left, and even hacked or tampered with—and still others clumsily fail to address their worlds, the nature of the game as a game is crucial to Lifesteal. Everything from bugs in the server’s custom plugin to glitches in the base-game itself can and will be exploited to their fullest extent, as story-fodder, weapons, and sources of conflict.

Metagaming means a lot of different things in a lot of different contexts, but essentially, this is the practice of using out-of-game information to inform your in-game actions. In other words, a lot of roleplay scenarios run on the idea that there are things you-the-player know, that your character can’t or shouldn’t know. In other Minecraft series with different formats, like the QSMP, which does possess a defined setting separate from Minecraft as a game, players who are interested in metagaming sometimes clash with more dedicated roleplayers, because the two playstyles function on different logic. On Lifesteal, roleplay and metagaming aren’t at odds. In fact, they’re intertwined; metagaming is a perfectly legal move on this board.

There’s no proximity chat mod here to simulate natural conversation based on physical distance, instead players communicate over discord. They can screen-share to each other, eavesdrop on one another’s conversations by quietly joining the wrong voice call, and in one memorable instance, they can even block each other. There are etiquette rules when it comes to meta information you are or aren’t allowed to use to your advantage; while watching another player’s livestream (“streamsniping”) is off limits, any information put into a Youtube video appears to be free game, for example. But that doesn’t change the basic fact of the Livestream’s existence, or its relevance to the server’s internal affairs.

Taking something like the Life Series as a counterexample, where every season establishes a new set of rules to play by, and then the events of the season explore these mechanics as players compete to win that version of the game, Lifesteal’s lack of any identifiable win state stands out. A win in the Life Series is contingent with the end of the game, and then everything ticks back to an even playing field when the next season begins, in neat self contained units. A win on Lifesteal guarantees you nothing but that single win. You can always lose the hearts you gained, or the bug you’re leveraging over other players could be patched the next day and take your advantage with it. In winning, you become a problem for someone else to solve.

From The Passion by Jeanette Winterson:

You play, you win, you play, you lose. You play.

The end of every game is an anti-climax. What you thought you would feel you don't feel, what you thought was so important isn't anymore. It's the game that's exciting.

And if you win?

There's no such thing as a limited victory. You must protect what you have won. You must take it seriously.

Victors lose when they are tired of winning. Perhaps they regret it later, but the impulse to gamble the valuable, fabulous thing is too strong. The impulse to be reckless again, to go barefoot, like you used to, before you inherited all those shoes.

In contrast to the Life Series’ comparative compliance with their rule-sets, the requirement of constant momentum on Lifesteal reinforces the rule-breaking, rule-bending tendencies already baked into it as a soft anarchy server of sorts—that is, a server where builds can be griefed, items can be stolen, and nothing is expected to last. There’s only so much you can do inside of the rules, be they the architecture of Minecraft itself or those rules self imposed by the players, and how compliant players are willing to be with these rules waxes and wanes over time. Tools like the F3A command to reload chunks, allowing you to see players through walls, or replay mod, providing a similar service to find underground structures are utilized relentlessly in Season 4, despite sometimes dubious legality. From time to time you’ll see someone outright flyhacking, if the mood strikes. A defining moment of Lifesteal’s first season was Mapicc–the owner at the time’s misuse of admin commands; this stuff is baked into their DNA.

Ash: You know what Mapicc did in Season 1?

Zam: [laughs]

Ash: Exactly.

Zam: I wasn’t even there, dog! That doesn’t even work on me, I wasn’t even there

Ash: You know what Mapicc did in Season 1? Despicable stuff.

Zam: I do know what Mapicc did in Season 1 dude—this could be just as bad! Do you not realize that? That this is like, nearly as bad?

Ash: No, but we’re good at storytelling though, so…

Zam: Does that right all your wrongs?

Ash: Yeah!

(Ashswag vod, 3/29/2023, 1:06:00)

Getting an admin to dish out consequences would also be, in many cases, boring. If a player’s rule-breaking is worked into a plotline, seeking a solution to the problem on out-of-game bounds would serve only to deflate the tension—for the person “cheating” and for you. This is a sticking point that comes up over and over again for Parrotx2, who was the server owner during Season 4, because if the admin is expected to adhere to the rules and dish out punishments when appropriate without bias, an entire dimension of play is cut off. In Season 5, when ownership of Lifesteal moved from Parrot to Spoke and Ashswag, Parrot’s first move was to break rules to his heart’s content. Spoke, too, displayed a behavioral change; the man who had spent months of Season 4’s runtime lying to Parrot in order to achieve /op and backdoor the server, having attained a type of legitimate godhood, steps out of his trickster role and begins to act as a mostly reasonable server admin. In fact, Everyone’s attitudes change in Season 5, especially when it comes to exploits. Season 4 was so frustrating, exhausting, and unsatisfying that the principle of the thing is soured, and that type of rule-breaking falls out of style–except in the hands of newer players, who lack that history.

In their particularityIn The Edges of Fiction by Jacques Ranciere, he opens with an argument on fiction by way of Aristotle:

Poetry, by which he [Aristotle] means the construction of dramatic or epic fictions, is 'more philosophical' than history because the latter says only how things happen, one after the other, in their particularity, whereas poetic fiction says how things can happen in general. Events do not occur in it at random. They occur as the necessary or verisimilar consequences of a chain of causes and effects.

This I find to be useful in reference to Minecraft Roleplay, because in its lack of scripting Lifesteal provides something much closer to an account of history than to a classical drama on Aristotle’s terms. Here, our story takes the form of an authorless series of events as they happen one after another—in their particularity, where meaning is imposed in two ways:

Firstly, through the intention of the players as they live out the events in question, as it is presented on livestream—you can make a plan and attempt to carry it through, you can imagine how you hope things will end up, you can try to impart a particular significance to a particular action, you can discuss your motivations and values. In sum, you can recount the personal emotional experience of your life on the server to the audience. What you can’t do is guarantee the results as you toss the dice, or dictate the emotional experiences of the people around you the way an author could direct their cast of characters down the path to a necessary end.

Secondly, through the retelling of events after the fact. As we’ve previously established, video editing is an authorial process. Editing allows one to cut things that complicate or contradict the narrative, reorder events, produce alternative visuals, and retell a story with all of the creative control afforded to anyone who has ever, for example, bent the details of the dream you’re describing to a friend in order to transmute the nonsense into a coherent, funny anecdote. Even before heaps of circular debate, base building, potion brewing, and gear-grinding are sentenced to the editing-room floor, the past is constantly being retold by the players, to both one another and the audience, subject to the forces of memory and bias. In both cases—the grand, final video-narrative and the small, interpersonal conversational-narrative—you have the unique caveat that the way things actually went may well be preserved on video to compare against the story you’re being told in the moment, revealing precisely how someone’s emotional lens can warp the recollection of an event.

If it weren’t for the audience and the artistic product being produced, this would all be indistinguishable from the way that life already works. As a person in the world, you will constantly contend with your own limited ability to perceive the world, and the knowledge of your perception by others. You will try to control these things and you will fail. Watching Lifesteal, you understand that every player implicitly has “trying to make Youtube videos” as part of the motivation for their actions, and that every player understands this motivation in every other player. There’s no accounting for anything that happens on Lifesteal without acknowledging this.

For example: in Season 4, the team Leviathan—consisting primarily of Mapicc and Roshambo—exiles ItzSubz_ from spawn. The same spawn he had spent hours rebuilding, terraforming new terrain over the scorched earth left over from when those same players had destroyed it. Another player, Zam, previously teamed with Mapicc and Ro but now turned against them, watches powerless as Subz loses a fight to them. These are all very coherent story beats on paper, because this is how the Subz video tells it. On stream, you watch Mapicc and Ro reluctantly agree to exile him so he has an ending to the video, and then you hear them laugh at Zam every time he brings up Subz’s exile, because they don’t actually care.

Because of this dimension to things, Lifesteal can feel at times like a competitive form of storytelling. While players do want each other to come out of the game with good videos, their visions can’t always align, not when the stories they tell are built on competitive gameplay to begin with, or when they become so emotionally invested in what’s happening that they cease to behave on the logic of storytelling and video-making. There’s a constant, recurring anxiety from certain players about how truthful other players are or aren’t being in the framing of their videos. A discomfort or frustration with misrepresentation, the fear of not being able to control the way that others frame your actions, when you want very badly to come off a certain way—or play a certain role—and you have no say in how other people feel about you, how they read you, or how they portray you. An ever-present awareness that your image is never only in your own hands.

It’s all very fragile. You're trying to tell a story collaboratively, but because it's all based on genuine reaction nobody is ever on the same page about how it should go, just that it should go in the first place, and that not knowing about things before someone wants you to know makes for a better plotline. But the medium—the live audience, the same thing that renders Lifesteal a work of art-or-content and not simply a part of these people’s lives the way any other Minecraft server might be to anyone else—is working against you!

Lifesteal’s Information economy extends out of the server’s bounds and into the hands of the audience, who have the power to make or break these storylines by telling the wrong Lifesteal member the wrong piece of information, squandering the chance for a natural reaction. In most cases, the response to this tension with the livestream medium is easy: don’t stream things you can’t afford getting out, even though that makes it less fun. Nobody likes having to tiptoe around accidentally revealing the wrong thing on stream, but you have to, because you can’t trade the entertainment value of the natural reaction for the ease of pre-coordinated storytelling, and to do so would be to render Lifesteal unrecognizable. In the slow periods where few to none stream on Lifesteal, the audience’s window into the server shrinks down to a pin-point; long editing times and infrequent uploads mean that in the absence of streaming, the audience is cut off from the server chronologically, left only with storytelling done in retrospect, or through the eyes of a single player. If no one livestreamed anything, if it was given up entirely, an entire dimension to Lifesteal’s world would be lost.

You can convince another player to keep a secret, but you can’t put the cat back in the bag once something is shown on stream. Where a server member can pretend not to know something, the audience’s knowledge is what enshrines something as true; everything that happens on Lifesteal happens. There are no take backs, even when everyone wishes there were.

Zam: Okay, I’ll block the term “Lifesteal spoilers.” It’s crazy that other SMPs don’t have to deal with this.

Planet: I know! We’re such a—in such a unique situation.

Zam: We’re so weird. [laughs]

Planet: We’re like—either you’re super like, scripted and like, lore, or they’re—

Zam: They’re too famous to see it. And like, stream-sniping doesn’t matter on those servers.

Planet: There’s not really any other like, huge competitive SMPs that are also content focused.

(...)

Zam: “Usually it’s fans having to mute spoilers.” That’s funny. It’s funny that we have to do it.

(Zam vod, 3/29/2023, 1:02:00)

What this means is that a character who refuses to keep anything from the audience if he can help it, who maintains this continuity at the cost of his interpersonal relationships, is a novel thing.

(A screenshot of PrinceZam in front of a wall of signs, from a Vitalasy stream. I like this guy an ordinary amount, if you were wondering. As evidenced by the doll I made of him while I was putting off writing this blog post…)

You, as the viewer, are positioned inside of Zam's head in a way you aren't always guaranteed with other Lifesteal characters, even when they do get consistent livestream POVs. This is for the simple fact of his reluctance to hide anything from you; where Zam is constantly processing his thoughts live, in conversation with his chat, Subz is preparing his thoughts ahead of time to reveal at opportune moments. It's impossible to forget, watching a Vitalasy stream during Season 4, that he is hiding things from you.

This is why, when Zam ends up stuck trying to balance the scales as one third of a team who's other two members are dedicated to a long-term plan secret enough that it has a 5-month time investment beginning before the season even started, it's so compelling; they have a legitimate reason to keep things from him. It isn't a matter of mistrust or manipulation, or at least not entirely, it's the simple fact that Zam cannot keep a secret. And their reasons for bringing him into the team in the first place, despite the fundamental conflict in values Zam introduces into the Eclipse Federation, are sympathetic: there was no one else there to help him when he hit his lowest point.

Despite the fact that Zam and Subz both express, at various points, that they feel closer to each other than either does to Vitalasy during Season 4, having spent much, much more time together, Zam is still a constant outsider to Subz and Vitalasy's relationship. Not just because they have history together, and a kind of predetermined loyalty making it so that Subz betraying Vitalasy in favor of Zam at any turn would be an unthinkable act (to the point that it isn't even allowed to be a question), but because of this established information hierarchy. So, throughout all of Season 4, the Eclipse Federation is living on borrowed time: Vitalasy and Subz are keeping their plan from Zam on the grounds that he can trust their judgment, while Zam harbors a fundamental ideological conflict that would put him at odds with the team's goal if he knew what it was. An ideological conflict fueled in large part by his experiences with the very thing the Eclipse Federation took him in to keep him safe from—the use of exploits by Leviathan—which in turn allows Zam to consider placing his trust in them despite their hidden intentions as the repayment of a debt he invented wholesale. Needless to say, this is not how you create a stable relationship.

Medium ConflictPlanet: If Lifesteal was scripted, we would be the worst writers in the whole world. 'Cause what the fuck is going on.

(Zam vod, 2/12/23, 2:06:00)

It’s February of 2023, and something goes wrong on the Lifesteal SMP. First, a warden spawns out of nowhere, only to vanish again. The next day, a block of bedrock appears at spawn:

(Zam vod, 2/12/23, 27:44)

PrinceZam finds himself the unwitting witness to ultimate power, as Ashswag–one of three players with access to exploit-granted godhood, along with Spoke, and Zam’s teammate Vitalasy–reveals this power months sooner than their plan called for. This isn’t out of the ordinary for Ash, who makes a habit of playing god; one memorable instance in Season 3 saw him colluding with the coder of the Lifesteal plugin to sneak in a personalized bug under the server admin’s nose. But Zam, as a witness, is primed to hate the use of exploits. Not just on moral grounds, but for what they do to the balance of Lifesteal’s gamemode. Season 4 had previously found him complicit in the use of a dupe glitch that the server’s item economy never recovered from, and after leaving his former teammates over said duped items, he was left to fight off an enemy who had made themselves functionally unbeatable through the use of another exploit.

The ensuing stream is an extremely odd one: Zam hates what’s happening, Vitalasy tries to reassure Zam that he has a plan, and that he can’t explain that plan on stream, and that there was supposed to be a big, dramatic reveal for Zam. The vod is deleted, and then undeleted, as they try to reconcile what’s happened and come to terms with the fact that they can’t pretend it didn’t happen. To make matters worse, Vitalasy wakes Subz up in a panic, who–not wearing his glasses–presses the go live button instead of the recording button, while he and Vitalasy discuss the very same secret plans that have just been jeopardized by Ashswag.

Spoke: I gave him this power. We… were supposed to wait two months.

Zam: Oh wow. Wow.

Spoke: All it took was an hour with this power.

Zam: Yeah.

Spoke: You’re–

Zam: So I've heard.

Spoke: No one–we’re never gonna see this again.

Zam: Okay, that’s what I thought.

Spoke: The bedrock will be gone by tomorrow. Everything will be back to normal.

Zam: That’s crazy how–yeah, okay.

Spoke: You’ve never–the past hour or so–

Zam: This never happened. This didn’t happen. Okay.

Spoke: This never happened to you.

Zam: [unenthused] I’ll just forget about it.

(Zam vod, 2/12/23, 1:32:40)

In the moment Spoke and Ash try to walk it back, but in the wake of this stream, the cat is thoroughly out of the bag; the players know, the audience knows, and an endermite that can kill anyone in one hit roams around Lifesteal spawn like an unusually nasty stray dog.

(“Poopies” the immortal endermite sits amidst a pile of items, which represent the corpse of baconnwaffles0.)

Zam: I don’t want to ruin things. [reading a chat message] “This is so weird?” Yeah, this is like the weirdest thing that has ever happened on Lifesteal (...) they were not supposed to do this. But I don't–yeah, I don’t know if I can just forget about this.

(...)

Zam: It’s so silly, because if we scripted our videos then snitching wouldn’t be a problem, right? But if we did script our videos, people would be mad. (...) the same people that streamsnipe would be really mad if we scripted our videos, but that’s the only way to counteract streamsniping, so I don’t know. ‘Cause none of us want anyone to streamsnipe! Nobody does! Nobody appreciates it, nobody likes it–it’s like, no one gains anything from it, it’s only a loss. It’s only a net loss. ‘Cause a cool thing that could happen in the Lifesteal storyline just like, gets ruined because people know things that they shouldn’t. Like–if i could like, completely forget about everything that’s happened today, I would! I wish I could! I genuinely wish I could! ‘Cause it would have been so much cooler if they revealed this the way it was meant to be revealed–I guess–I don't know how it was meant to be revealed, but I’m assuming they were planning something really big, and it just kinda got ruined.

(Zam vod, 2/12/23, 1:35:50, 1:42:20)

This stream marks the beginning of the end for Season 4, though it won’t come for another 3 months. It’s the point where things start to fail, where it becomes clear that Vitalasy is somehow at odds with his fellow exploiters, where the gravity of the things Vitalasy is keeping from Zam become impossible to brush off, and where the frustration and disappointment over how the plotline is moving becomes more interesting than the attempted plotline on its own grounds.

Out of bounds

(An image of Minecraft’s world border–an optional feature limiting the size of a Minecraft world, through the imposition of a wall players can’t cross. Many versions of the game feature glitches which allow a player to move beyond it anyway.)

Man, Play, and Games by Roger Caillois was a landmark work of Games Studies published in 1961, well before the popularization of the video game medium, or the struggle to define Games Studies as a field of research in its own right that followed. What Caillois is interested in is simple: taxonomy. What is a game? What is play? And how many different kinds of each can be identified? Like any work of taxonomy, it suffers from the usual pitfalls of the art: things in the world do not come prepackaged in clearly delineated categories. Still, as the primary function of language—the replacement of a subject as it exists in the world with a symbol to refer to it in shorthand—suggests, we have a proclivity for these distinctions. This is the same urge responsible for the fiction-nonfiction problem we tackled last time, the great and terrible grey areas.

Play, by Caillois’ definition, has six characteristics:

It must be: Unproductive, property or wealth may be exchanged within the game but no goods are produced through the game, separating it from both work and art as categories of human activity.

As for the professionals-the boxers, cyclists, jockeys, or actors who earn their living in the ring, track, or hippodrome or on the stage, and who must think in terms of prize, salary, or title—it is clear that they are not players but workers. When they play, it is at some other game.

Free, a voluntary activity entered into purely on one’s own desire; if you’re forced to participate, it ceases to be play.

It would become constraint, drudgery from which one would strive to be freed. As an obligation or simply an order, it would lose one of its basic characteristics: the fact that the player devotes himself spontaneously to the game, of his free will and for his pleasure, each time completely free to choose retreat, silence, meditation, idle solitude, or creative activity. (…) It happens only when the players have a desire to play, and play the most absorbing, exhausting game in order to find diversion, escape from responsibility and routine. Finally and above all, it is necessary that they be free to leave whenever they please, by saying: “I am not playing any more.”

Separate, isolated from the rest of life by the limits of a dedicated time and space.

There is place for play: as needs dictate, the space for hopscotch, the board for checkers or chess, the stadium, the racetrack, the list, the ring, the stage, the arena, etc. Nothing that takes place outside this ideal frontier is relevant. To leave the enclosure by mistake, accident, or necessity, to send the ball out of bounds, may disqualify or entail a penalty. (…) In every case, the game's domain is therefore a restricted, closed, protected universe: a pure space.

Uncertain, in such a way that the results of the game cannot be known before the game produces them.

Doubt must remain until the end, and hinges upon the denouement. In a card game, when the outcome is no longer in doubt, play stops and the players lay down their hands. In a lottery or in roulette, money is placed on a number which may or may not win. In a sports contest, the powers of the contestants must be equated, so that each may have a chance until the end. Every game of skill, by definition, involves the risk for the player of missing his stroke, and the threat of defeat, without which the game would no longer be pleasing. In fact, the game is no longer pleasing to one who, because he is too well trained or skillful, wins effortlessly and infallibly.

And finally, either Governed by rules, which superimpose themselves over the laws and behavioral expectations of reality…

The game consists of the need to find or continue at once a response which is free within the limits set by the rules. This latitude of the player, this margin accorded to his action is essential to the game and partly explains the pleasure which it excites. It is equally accountable for the remarkable and meaningful uses of the term "play," such as are reflected in such expressions as the playing of a performer or the play of a gear, to designate in the one case the personal style of an interpreter, in the other the range of movement of the parts of a machine.

Or, involving Make Believe, where an imagined, fictitious reality serves the same purpose as the rules of a game would in replacing those imposed by life outside the game.

Many games do not imply rules. No fixed or rigid rules exist for playing with dolls, for playing soldiers, cops and robbers, horses, locomotives, and airplanes-games, in general, which presuppose free improvisation, and the chief attraction of which lies in the pleasure of playing a role, of acting as if one were someone or something else, a machine for example.

(…) in this instance the fiction, the sentiment of as if replaces and performs the same function as do rules. Rules themselves create fictions. The one who plays chess, prisoner's base, polo, or baccara, by the very fact of complying with their respective rules, is separated from real life where there is no activity that literally corresponds to any of these games. That is why chess, prisoner's base, polo, and baccara are played for real. As if is not necessary.

Thus games are not ruled and make-believe. Rather, they are ruled or make-believe.

The idea that rules could themselves be responsible for creating a fiction has stuck with me since I first read this book, half a year before I started writing this blog post, because it put into words something I had been struggling to wrap my head around in relation to Minecraft roleplay. Specifically the kind of Minecraft roleplay that functions the way Lifesteal does, where the server’s ruleset alone can create a fiction through the imposition of its unique situation, which is markedly different from the ‘real’ relations taking place outside of the context of the game. In this way, you don’t require the construction of a fictional world, walled off from the knowledge of players-as-players and game-as-game, in order for the proceedings to become a fiction. Conducting yourself by a new set of laws is enough.

(This also explains the mechanism by which any interaction with Minecraft becomes to some degree fictionalized, even the vanilla kind with no audience to speak of, considering game mechanics as interchangeable with rules. The additional rules of a custom gamemode only add to the fictionalization already happening when a person interfaces with the base game.)

On Lifesteal—and this is true of most games—these rules don’t exist in a vacuum, overwriting the laws of reality with no trace. At what point does deciding to play a game, negotiating the rules, and constructing the fiction, become playing the game, existing within the fiction? In practice, these processes overlap. In some cases, you go back and forth between both states often enough that the distinction breaks down. How often is the rulebook consulted before you can make your turn in Dungeons and Dragons?

As a child playing pretend, I recall a great deal more time spent on the negotiation of what we were doing, the debate over who got which role, and the assignment of our environment’s features to imagined locations, than was spent actually carrying through on these negotiations. The negotiation itself was, in my memory, fun. A part of the game all its own.

To follow Caillois’ model to the letter produces a state of things where a person can be, through pressure or employment—these sticky entanglements of the real world creeping into the game’s ‘pure space’—playing a game and yet not truly playing; “When they play, it is at some other game.” You can, theoretically, end up with a game in which none of the players are experiencing a state of play, and yet the game continues on. The difference is indistinguishable to the outside observer, decided entirely by the player’s internal state.

This linguistic sticking point is revealing to me, because if you were to compare these conditions against something like Lifesteal, which can be both a game and a job, even a game and a job and an artistic process simultaneously, things seem a bit less clear cut. My point is, nearly every one of the alternative states to the qualities of play brought up by Caillois appear in Lifesteal, almost as often as the qualities themselves do. His negations of play; productive labor, constraint and boredom, bleeding edges between “game” and “life,” the reality-check or denunciation of the rules that stand to break play’s magic spell, all of these things happen. Instead of splitting Lifesteal into two halves, work and play, behind the fourth wall and in front of it, the fiction confined to the magic circle’s interior and the reality outside, the lens just has to widen enough to see beyond the game’s container. There can never be a game in the first place, without the negotiation of the rules.

To repeat myself, Minecraft roleplay is simultaneously a story taking place within a game, and a story about people playing a game. These two things are not contradictory, this is the natural state of things any time a person interacts with any game, or any fiction for that matter, where there is both a story produced and the history attached to its production. The only question is whether you pretend at self-containment or not, and that is what playing along with the fourth wall does.

You might extend that to say, Lifesteal is a story about people telling stories.

Remember that thing Caillois said about uncertainty? Does it ring any bells in relation to Lifesteal’s roleplay style, when it comes to the value placed on undefined outcomes? In this sense, Lifesteal’s storytelling is itself gamified. it is essentially possible to “win” or “lose” control of the narrative, on the assumption that your opponents will comply with narrative logic–the rules of the storytelling game, where there is an implicit agreement to prioritize audience interest above all. When it becomes impossible to combat the exploits through traditional means like PVP by the end of Season 4, players discuss the possibility of forcing a “loss state” through narrative satisfaction, finding a conclusion to the plotline wherein the exploits no longer make sense to use, are no longer interesting, instead of allowing the exploiters to carry out their win at the expense of everyone else. And this is why exploiting and rule breaking are allowed so long as you can make it interesting, because it works in compliance with these unspoken narrative rules.

Let's borrow an example from Season 5. During the election plotline, when Squiddo slanders 4C by editing clips together out of context, 4C’s in-character indignation is constantly interrupted by his real emotion, which is giddy joy over how cool and compelling this move from Squiddo is, how good for content it is. In contrast, when 4C wins the election with a set of policies Zam, Mapicc, and Bacon find boring, they’re more upset over the lack of anything substantial to bounce off of than they are over Mapicc’s campaign losing in and of itself.

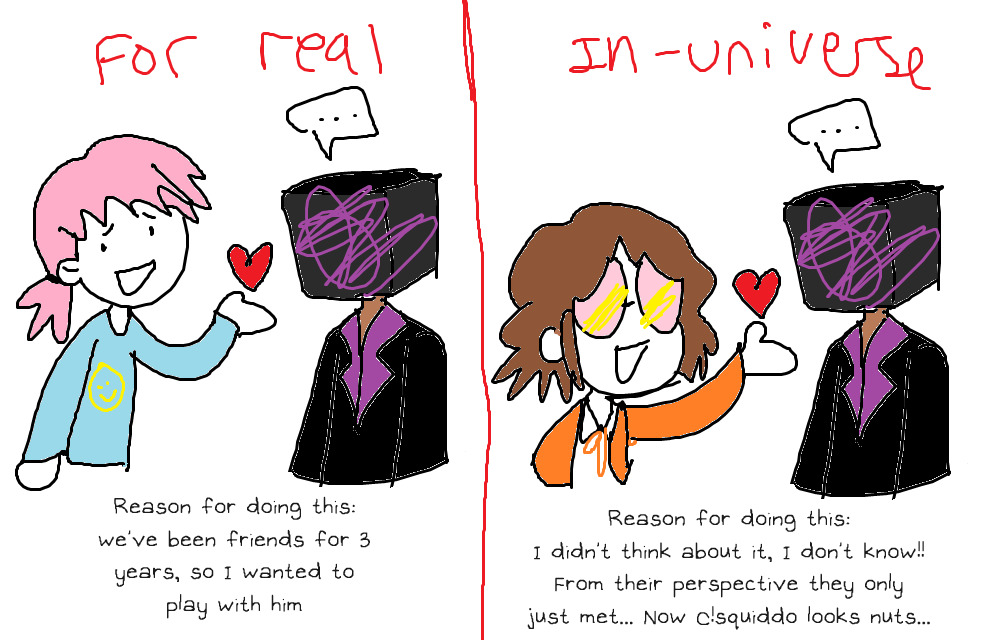

In response to a question about her experience on Lifesteal, Squiddo explains it like this:

Lifesteal Squiddo is just a very dramatized version of my real life self… Like, how in real life when something mundanely bad happens, you might exaggerate and mime fainting for a laugh; that’s what Lifesteal Squiddo is. I do that because it’s entertaining and it’s my job to entertain you. When something bad happens, I don’t care, it’s just our jobs- but to Lifesteal Squiddo it’s the end of the world.

(...) With the nuke, the entire time I was thinking “How can I work this into a video? This will be a dramatic plot twist, people will like this…” and that sort of thing. But to Lifesteal Squiddo there is no Youtube, so she was just angry.

(...) Although, I actually was happy when Ashswag gave me hearts, I really did think he was going to kill me. I’m glad I get to keep playing. I couldn’t sleep that night because I kept smiling… That’s probably the only time Lifesteal Squiddo and myself have felt the exact same thing

Her conception of Lifesteal’s fourth wall is much more rigid than mine. Lifesteal is at its best to me when, like in Season 4, the gap between these two motivations is actively called into question. Or, like Squiddo describes, when the in-game and out-of-game emotions align, and you can tell. In this post, she both reveals that she thinks of Lifesteal Squiddo as a character without history prior to or outside of Lifesteal, and articulates that her real relationship with Ashswag is intrinsic to Lifesteal Squiddo’s relationship with Ashswag, requiring you to start inventing new motivations wholesale if you ignore that real relation. “I didn’t think about it, I don’t know!! Now c!squiddo looks nuts…” but this wouldn’t be a problem, if you weren’t inventing the fourth wall…

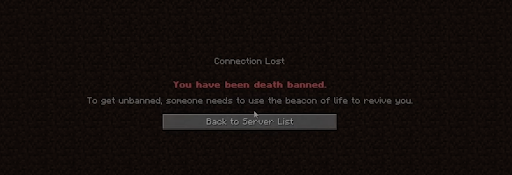

The doorwayThe ability to cease play is built into Lifesteal both through its unique game mechanics, and through the ever-present functionality of Minecraft. One of the most memorable parts of Season 4’s finale-week comes when Vitalasy repeatedly urges Zam to just stop playing if he isn’t having fun, a clear and concise verbal acknowledgment of what Minecraft is, what Lifesteal is, and how it functions:

Vitalasy: The people who want to live in this world should be able to live in this world. The people who don't want to can leave!

Vitalasy: Hit the disconnect button.

Vitalasy: If you don't want to be here, that's fine. You leave on your own terms. Whatever, you don't belong? I thought that way too and I left. But I'm not gonna make everyone have my problem.

(Zam vod, 5/13/2023, 1:16:30)

Throughout Season 4, Zam toys repeatedly with the idea of banning himself, logging off, taking a break, dying… but he never does it, because he doesn’t actually want to stop playing–he wants, more than anything, to keep playing. But he’s unhappy with the state of the game, not having fun, and he can’t find a way to fix it…

To better explain the function of Lifesteal’s game rules in creating and reinforcing its fiction, particularly when it comes to the meaning granted to in-game death, we need a counter example. During its lifespan from 2020 to 2023, The Dream SMP functioned as a “scripted” roleplay server, one where certain deaths mattered to the story and others didn’t. Storytelling on the DSMP evolved over time, from a beginning as an ordinary vanilla survival server–where players can, in usual Minecraft fashion, die and respawn ad infinitum. Even as the DSMP’s storytelling developed, from loose conflicts over items or land, to lightly scripted events with pre-planned character deaths at especially dramatic moments, to the shiny pre-recorded cinematics of Quackity’s Las Nevadas, the game mechanics remained the same as they always were.

In other words, the Dream SMP’s fiction came in large part from the sentiment of as if, not from any uniquely imposed rules. But an obvious issue arises… sometimes you’re just living on the server–mining, building, playing around, and if you die, it doesn’t mean anything. It isn’t Death with a capital D, a story beat possessing narrative significance, and there is no hardcore gamemode in play that would impart a special weight to any death regardless of surrounding circumstance. Your character simply tripped and fell, or drowned, or you weren’t expecting that hit to kill someone right then and you have to laugh it off. Some deaths are ‘canon’ to the server’s storyline, and some aren't.

To make matters even more confusing, that is precisely how they handled the problem. That was the terminology they used, canon deaths. Arbitrarily pulling from a reddit comment by a fan musing on the issue of infinite death, it was decided that Dream SMP characters possessed three canon lives, three plot-relevant strikes and you’re out.

The use of terminology distinguishing “meaningful death” from “fake death” does something strange, because it implicitly acknowledges the fake deaths. in a world where it means something when you die, you simply call them lives. What use is the distinction, if that’s all there is? But because you’re moving between speaking in-character and out-of-character so frequently, and you’re playing pretend about death mattering in a world where it materially doesn’t matter, you have to specify, and in doing so call attention to the fact that you’re having this problem in the first place.

What does this do to the server as a setting? By making it so that not every death on the server matters to the story, the Dream SMP is outright telling us that not everything that happens on screen can be considered equally ‘real.’ But who decides what carries meaning and what doesn’t? Where do you draw the line? It’s only natural that players will constantly interpret things differently to one another, in ways that frequently conflict with or contradict each other’s storylines. Only here, there is no shared material reality to fall back on; you’re not debating the significance of something that happened, you’re debating whether it happened at all.

Working inside of a hardcore-style life system where every death is finite, if you make a silly mistake and die that way, or die as part of a joke, or the tone of what's happening switches on a dime, the death still has material consequences. 3rd Life, for example, is able to produce its emotional resonance almost entirely off of this contrast. Grian kills Scar with a creeper on accident, as part of a joke, and that sparks the relationship as teammates that will carry them through the rest of the season; Scar is the first player to turn red because he never watches where he’s going; and in the end, when the two of them have a half-hearted fist fight for final victory, they’re laughing the whole time.

This is why the Dream SMP's permadeath system felt pointless as soon as the concept of revival was introduced, because none of it is naturalized as part of the game. Losing your final canon life on the DSMP doesn’t even mean that you can’t play anymore–instead, ghosts are introduced and dead players are stuck in a state of limbo.

Being death-banned on Lifesteal means leaving, not dying as such; In linking in-game death to the cessation of play, death is granted meaning. Death is how you leave, and for the players left on the server without you, "death" and "absence" are related conditions to begin with. In Lifesteal Season 4, characters talk about and go through with banning themselves a lot, and it’s almost always in response to a feeling that the game is no longer fun–it’s simple: you stop playing if you want to stop playing. It’s the tension imposed by the hardcore gamemode in reverse, where the pressure comes from the desire to keep playing, and the fact that you could lose access to the game if you fail.

Vitalasy’s death near the end of Season 4 is framed as something he had to do because he felt like he didn’t belong on the server anymore, but killing yourself is still the mechanism in place for communicating that kind of door-slam. You can always log off and choose not to log back on, but it doesn’t carry the same immediate connotations that a ban does; if you ban yourself you don’t have to explain yourself, the ban does it for you. (And it’s also immediately recognized as a server-level, story-relevant action. When Vitalasy does leave Lifesteal once and for all in Season 5, he doesn’t just vanish, instead he couples it with a lovingly crafted final story beat for his teammate culminating in his death at her hand.)

After Vitalasy’s “death” in Season 4, Zam talks about him being dead, regardless of the fact that Zam knows Vitalasy can come back and so does the audience, because the act of banning yourself and the resulting absence means something. “Death” means absence, but the door is always still cracked open. You can't bring yourself back, but someone else can open the door. They can't make you walk through it, but they can open the door. when Subz bans himself soon after Vitalasy this comes to a head, because he’s made it very clear that he isn’t coming back, no matter how much Zam is able to delude himself into thinking that all he has to do is revive him.

As a result, suicide on Lifesteal can land with an odd resonance, despite the subject matter and the medium. When people kill themselves it is very rarely about wanting to be dead so much as it is about needing something to change and feeling trapped, like there's no way out of your circumstance through life so you have to turn to death. Or, like the way out through life is so much harder and more uncertain and you don't want to do it, while death is the most certain thing in the world. Or, like you just want everyone else to understand how you feel.

(It’s also apparently very easy to forget that you are in fact roleplaying killing yourself in Minecraft whenever this happens. At one point in Season 4, Zam writes out what is effectively a suicide note, and then his twitch chat calls it a suicide note and he gets too embarrassed to ever let the audience read it. Vitalasy sheepishly explains that his character didn’t kill himself, just left…)

So, suicide in a world where you can just come back later occupies a sort of How To Respond To Criticism by Daniel Mallory Ortberg fantasy:

Run into a cave and break your ankle so that people have to come find you and they see you lying at the bottom of this beautiful cave and maybe there’s a waterfall and the light from the crystals makes you look really beautiful and they say “Are you okay?” and you say “I think so” and they say “oh my God have you been here alone this whole time with a broken ankle” and you say “it’s okay” and they say “you’re so brave” and you are brave and you look so beautiful surrounded by cave crystals and everyone stands over you and says “oh wow” and “you poor beautiful thing” and “I’m so sorry we let you run into the cave but I’m so glad we found you” and let them carry you home and promise to be your best friends forever and that everything’s their fault and also they named the cave after you and you’re prettier than all of your enemies and your enemies all died of jealousy while you were in the cave.

Of course in reality, even on Lifesteal, that is not the reaction you get. Let’s put a pin in it for now.

Immersion Conflict

It’s not that Lifesteal doesn’t possess the concept of the fourth wall. Clearly, they all know such a thing is “meant” to exist—does exist to an extent in some videos thanks to the editing process—but when it comes to the full picture of Lifesteal, the streams and the videos, where you have to consider the video-making process in the same breath as you consider a players’s in-game reaction to the heart they just lost, or their conflictions about loyalty and betrayal, the fourth wall and what happens when a player verbally invokes it does something different….

(A gif from This Youtuber FAKED a Minecraft War by Leowook, animation by ThePrismicGuy.)

When a war on the server is ‘staged,’ something that does occur at one point between the players Parrot and Spoke in Season 4, not everyone is in on it. Reflecting on it later, Baconnwaffles0 says this:

Bacon: I say this fact to everyone, but I feel like not enough people know this. Parrot DM'd Mapicc to blow up Subz's base so Subz would join the APO.

Zam: Really?

Bacon: Yes. This is like—

Zam: I didn’t know that. That’s funny.

Bacon: This is where the lines of Lifesteal scripting are sorta blurred. It was never talked about in the lore, but it could have been. I tried to bring it up, I tried my best. But, like—you could argue that c!Parrot did that—

Zam: Zam: Somebody should tell Subz this. Does Subz not know this?

Bacon: Oh, maybe I should tell Subz this. But you could also argue that cc!Parrot did that so his video would be more interesting.

(Zam vod, 3/29/2023, 37:18 — for a refresher on c/cc language, see the introduction.)

And that “could have been” is doing a lot of work, no? That’s the thing. There is no distinction that matters between these two motivations, whether the character does something with motives based within the world of the server, or the Youtuber does something with motives that stretch beyond it. In either case, regardless of the intentions driving the action, the player is still acting on Lifesteal’s game-world with tangible consequences. The resulting action is the same, it has the same amount of ‘realness’ within the game. It happened within the bounds of the Lifesteal game, and can be responded to by other players on those same terms whether they respond in “character mode” or “Youtuber mode.” That said, can there be a difference between these two modes? Yes, in so far as the players believe there to be one. Take this for example:

Mapicc: You’re both aware that this conversation is going nowhere, right?

Ro: It might be going somewhere.

Zam: So what do you suggest?

Mapicc: I don’t know, this is kinda my fault. It’s poor judgment.

Ro: It’s my fault!

Mapicc: Okay, no, spawn is your fault. But I think—

Zam: We don’t need to pass around the blame!

Mapicc: Zam stealing the gear is mine. Didn’t need to trust him.

Ro: What do you mean? He’s part of our team! We trust Zam—I would trust Zam with my life.

Mapicc: I did trust Zam with my life. And then he took four god shulkers and turned against us casually.

Zam: What about Terrain?

Mapicc: What about Terrain.

Ro: I would trust Terrain with my life.

Mapicc: Did—would you really? You know Terrain’s mad at us, right?

Ro: Why?

Mapicc: ‘Cause you make him the villain in every single situation.

Ro: What—wait really?

Mapicc: The end, and the Medusa video.

Zam: He has my ideals. He has the exact same ideals as me, yeah.

Mapicc: Yeah. In the end video you made him like, some stranger.

Zam: He would be here too right now if he was available.

Mapicc: And in Medusa, he made it in like—he like—you were like, “someone saw us,” but it was Terrain.

Ro: I’m not trying to break the fourth wall here.

Mapicc: You’ve gotta tell him then.

Ro: Okay, well—I didn’t know that! Sorry? That was like, out of lore—just like, storytelling stuff.

(Zam vod, 11/27/2022, 2:23:41)

Here, an extremely ‘in character’ argument over Zam’s betrayal of Roshambo and Mapicc veers into an argument over the framing of someone in a video, and how they feel about that framing. If Roshambo didn’t bring attention to it, and flag it as “breaking the fourth wall,” it would be seamless—the distinction only matters when someone wants it to matter. To Mapicc, whether or not the two of them can trust Terrain has just as much to do with grievances over video editing as his decision not to trust Zam does with the items Zam stole from them in-game. And this makes perfect sense, when you consider Lifesteal’s storytelling to be part of the game.

Later, at the end of the season when Roshambo and Mapicc’s alliance is finally breaking apart, we see the same dynamic in reverse:

Mapicc: I don’t want to be here.

Ro: Um—like, on the server? Or like, in the plan?

Mapicc: Yeah.

Ro: Oh my god, why is everyone doing this?

(…)

Ro: Why? Just explain to me why?

Mapicc: ‘Cause this is pointless. The server’s pointless. There’s no morals, there’s nothing.

Ro: Can you explain what you mean by that?

Mapicc: You don’t want to put them in to save the server, you want to do it ‘cause you wanna do it.

Ro: Yeah, ‘cause it’d be a banger video idea.

Mapicc: Can you stop breaking the fucking fourth wall please?

Ro: [laughs] sorry.

Mapicc: Jesus Christ. Never mind, I’m not doing this.

Ro: Yeah, okay, but like, it will preserve everything—

Mapicc: No, we won’t! We won’t preserve jack shit! You wanna do it because you want the challenge, and you want to be above everybody else. It started in the end, when we removed the end and you killed everyone, you went “wow, the feeling of just—ruining everybody’s lives on the server is nice. I’m gonna keep chasing that feeling.” And that’s why we’ve been doing this. And at this point…

[Mapicc lights a block of TNT under himself.]

Mapicc: it is not worth it.

Ro: Dude, oh my—

[Ro tries to hit Mapicc away from the explosion.]

Ro: Get out of there, hello?

[Mapicc dies, pretending to be banned, and leaves the call.]

(Roshambo vod, 5/7/2023, 1:10:12)

Now, Mapicc telling Ro off for breaking the fourth wall has a different effect. Mapicc is angry that Ro isn’t taking things seriously enough, isn’t meeting him on the same level. The motive Ro creates for the character he plays, for the plotline of his videos—to preserve Lifesteal as it is, against the forces of time—rings false, and Mapicc calls him on it. It feels like a front Ro is putting up because it is one, literally. When Ro invokes the fourth wall (in cases like that earlier conversation, from Zam’s betrayal,) he does it in service to his version of the narrative, the one he’s trying to keep intact towards his own ends. But everyone else around Roshambo is privy not only to what he says, but what he does. They’re free to grab those contradictions and throw them right back at him. This feeling that Ro isn’t being honest is a thread you can follow throughout his relationship with Mapicc, who he repeatedly positions as volatile and requiring his presence as a balancing force to keep in check; knowledge of Ro’s video-related motives doesn’t detract from this character trait, it informs it.

The Emancipated Spectator is a collection of five essays by Jacques Ranciere, published in 2008. Of these the first essay, sharing the name of the book, is the most relevant: In order to comment on the relationship between artist, art, and audience, Ranciere must first reconstruct the history of discourse on the role of the spectator in theater, and the political character of that role.

In doing this, he identifies a pervasive assumption that the spectator is passive, while the actor is just so. The spectator can, in theory, be saved from this (moralized) passivity and pushed to action (or, salvation) through the experience of theater. This posits both the idea that the natural state of the spectator is somehow flawed or deficient, and that art has the power to repair it, to transform the spectator's passivity into activity. Given that the natural state of the spectator is supposedly flawed, the natural state of the performance is not enough on its own merit to inspire this action in the spectator. Instead, theater itself must be transformed until it can produce this result in the audience. This is a self-defeating objective.

More on that?

As Ranciere describes it:

There have been two main formulations of this switch, which in principle are conflicting, even if the practice and the theory of a reformed theatre have often combined them.

According to the first, the spectator must be roused from the stupefaction of spectators enthralled by appearances and won over by the empathy that makes them identify with the characters on the stage. He will be shown a strange, unusual spectacle, a mystery whose meaning he must seek out. He will thus be compelled to exchange the position of passive spectator for that of scientific investigator or experimenter, who observes phenomena and searches for their causes. Alternatively, he will be offered an exemplary dilemma, similar to those facing human beings engaged in decisions about how to act. In this way, he will be led to hone his own sense of the evaluation of reasons, of their discussion and of the choice that arrives at a decision.

According to the second formulation, it is this reasoning distance that must itself be abolished. The spectator must be removed from the position of observer calmly examining the spectacle offered to her. She must be dispossessed of this illusory mastery, drawn into the magic circle of theatrical action where she will exchange the privilege of rational observer for that of the being in possession of all her vital energies.

Such are the basic attitudes encapsulated in Brecht's epic theatre and Artaud's theatre of cruelty. For one, the spectator must be allowed some distance; for the other, he must forego any distance. For one, he must refine his gaze, while for the other, he must abdicate the very position of viewer. Modern attempts to reform theatre have constantly oscillated between these two poles of distanced investigation and vital participation, when not combining their principles and their effects. They have claimed to transform theatre on the basis of a diagnosis that led to its abolition.

While the point I want to make using Ranciere in relation to Lifesteal could have done without all of this context, I felt the need to bring it up because we talked about Brecht last time. Not that I was making any claims about the power for Minecraft Roleplay to inspire class consciousness in its audience and spur them on to revolution, just that it might be easy to overstate the effects of interactivity and a lack of clean wall between audience and fiction on the audience. The alienation effect does sufficiently alienate, I guess, the same way theater of cruelty also probably does something, it’s just that the leap Brecht tries to make from ‘alienation’ to ‘action’ doesn’t actually exist.

Also, because as the rest of the essays in The Emancipated Spectator touch on, this assumption about the Spectator being passive, and flawed in that passivity, is present in people’s approaches to making all kinds of art well beyond the stage. When it comes to video games as a medium, moves to define the unique qualities of that medium talk relentlessly of its interactivity, its capacity for player-choice, the degree to which a player can act upon the object. I’ll cut myself off there because really, this subject probably deserves its own blog post.

Anyway, back to the show.

To assume the passivity of the spectator, you have to more or less buy into the idea that in a work of art, the artist’s intention is packaged and delivered whole to the audience, where art is a means by which the artist directly imparts knowledge or experience onto the spectator. If this is true, the spectator’s role is merely to receive the message conveyed by the artist, not to interpret or collaborate. But art is not a certain form of communication, a direct bridge. There are three parties here, not two; artist, spectator, and the art as an object all its own between them:

The spectator also acts, like the pupil or scholar. She observes, selects, compares, interprets. She links what she sees to a host of other things that she has seen on other stages, in other kinds of place. She composes her own poem with the elements of the poem before her. She participates in the performance by refashioning it in her own way - by drawing back, for example, from the vital energy that it is supposed to transmit in order to make it a pure image and associate this image with a story which she has read or dreamt, experienced or invented. They are thus both distant spectators and active interpreters of the spectacle offered to them.

(...) It will be said that, for their part, artists do not wish to instruct the spectator. Today, they deny using the stage to dictate a lesson or convey a message. They simply wish to produce a form of consciousness, an intensity of feeling, an energy for action. But they always assume that what will be perceived, felt, understood is what they have put into their dramatic art or performance. They always presuppose an identity between cause and effect. This supposed equality between cause and effect is itself based upon an inegalitarian principle: it is based on the privilege that the schoolmaster grants himself - knowledge of the 'right' distance and ways to abolish it.

But this is to confuse two quite different distances. There is the distance between artist and spectator, but there is also the distance inherent in the performance itself, in so far as it subsists, as a spectacle, an autonomous thing, between the idea of the artist and the sensation or comprehension of the spectator. In the logic of emancipation, between the ignorant schoolmaster and the emancipated novice there is always a third thing - a book or some other piece of writing - alien to both and to which they can refer to verify in common what the pupil has seen, what she says about it and what she thinks of it. The same applies to performance. It is not the transmission of the artist's knowledge or inspiration to the spectator. It is the third thing that is owned by no one, whose meaning is owned by no one, but which subsists between them, excluding any uniform transmission, any identity of cause and effect.

The same way that the shared material reality of the game-world establishes truth no matter how differently two players interpret the same action, any fictional object provides a reference point no matter how two readings might differ.

On Lifesteal, players are “authors” of their own work at the same time as they are interpreters of every other player’s work; both collaborators and competitors, frequently contending with the gap between one interpretation and the next. This only works as well as it does because Lifesteal has the game’s reality as a point of reference to fall back on: where another series might ask you to act as if the game is a world you can’t just log out of, or as if a space 50 blocks across housing 4 people could be a full sized nation with the citizens to match, Lifesteal makes no such leaps.

Negation

The Season 4 stream I find most interesting is also possibly the worst one. Baconnwaffles0 starts going on about the economy at one point, and it's several orders of magnitude more entertaining than any of the roleplay stuff that happens. This stream made PrinceZam so mad he got a headache, and had to get up to put a cold washcloth on his forehead midstream. It made Vitalasy cry. To quote the video he later made about it,

Vitalasy: There was something sickening about all of this. Suddenly I genuinely began to cry. Maybe it was because the meeting reminded me of the real life aspect of not being heard, no one understanding you, no matter how much, how hard you try to speak. Maybe it was because at the time, I felt alone, just me and my thoughts. I tried telling myself "it's just a game," but after dedicating every day of my life to playing, to being this player, I couldn't help myself. I felt like throwing up. I felt like I needed to disconnect. If nobody else could see my perspective, then I didn't belong on the server.

It's something you could probably only get out of the livestream medium. If, say, a Hermitcraft recording ever goes this badly, we definitely don't see it. (and, it helps that Hermitcraft is populated largely by married 45 year olds who pay taxes and stuff, instead of a gaggle of teenagers and young adults who "won't go to therapy because it would ruin (their) lifesteal character(s).”)

Essentially, what happens is this: In the leadup to this particularly terrible stream, Zam betrays the Eclipse Federation. It happens in the wake of a long, long period of time spent trying to reconcile Vitalasy’s plans with his own moral opposition to the use of exploits in any context.

(Zam vod, 3/24/23, 45:00)Vitalasy: Zam, is there anything you wanna like, talk about? Before we get started?

Zam: Nope! [pause] do you have anything you wanna talk about before we get started?

Vitalasy: I wanna talk about anything you wanna talk about. It seems–

Zam: I don't know what that means.

Vitalasy: –like you may have something to talk about.

Zam: Do I?

Vitalasy: Do you?

Zam: I don't know.

Vitalasy: Just know honestly is like, number one... in a relationship…

Zam: That's a good point. Okay. Um. I still think what we're doing is irreversible, so if it does end up becoming a mistake, then that's gonna suck. That's like my only doubt, really. You know?

Vitalasy: Nothing is irreversible. Nothing. Maybe trust. But–

Zam: Trust is irreversible? What do you mean nothing is irreversible? We destroyed all the end portals, we can't bring all those back.

Vitalasy: I can bring all those back. Wait, wait?

Zam: Oh, I guess we can. Good point.

Vitalasy: Yeah.